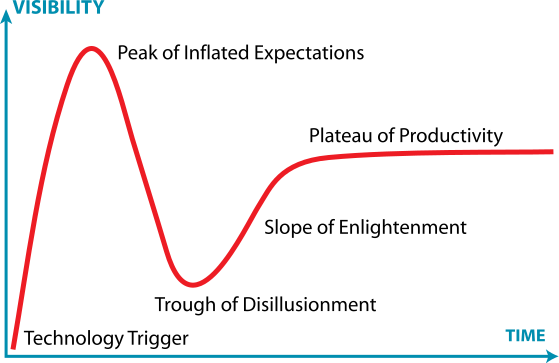

The revolution is here! The sky is falling! Popular and scholarly discussions of MOOCs vascillate between the extremes of euphoric technological utopianism or snarky vitriol that celebrates every MOOC failure (such as San Jose State University’s recent pilot with Udacity that resulted in the majority of students failing remedial math courses, see here). This state of discussion is not surprising if we think about MOOCs falling within the “hype cycle”.

Hype Cycle

If 2012 culminated in the peak of inflated expectations, 2013 is clearly the sharp trough of disillusionment. So what would lead us to the “slope of enlightenment” where we actually learn something about MOOCs?

We need to clearly articulate what we really have with MOOCs and also respect the large amount of research in education and learning that has largely been ignored in our discussion of MOOCs. How can we think about this in a systematic fashion?

Here are a few things to think about:

What do MOOCs really represent? I want to make the argument that MOOCs introduce a new sociotechnical context, within which we can experiment with designing how learning happens. If we think about it in these terms, it can help us weed out the noise that dominates the MOOC conversation, and better articulate the signal (what’s important).

What is the noise? Much ink (or digital real estate) has been used by many folks trying to get in on the ground floor of MOOC discussion: “MOOCs are the end of higher education. MOOCS illuminate the failing business model of universities. MOOCs are the democratizing force to bring education to the masses. MOOCs are a bait and switch scheme to dismantle education systems. MOOCs are nothing but content put online and slapped with a nice label and institutional support, no better than a textbook.”

These ideas are all fine and good in the abstract, but what do we really have when we think about MOOCs in a nuanced way? We have something in between. MOOCs (right now) clearly are not effective “courses” in the way that educators and education researchers know they should be. Courses involve access to content (a problem that MOOCs solve nicely), but also day-to-day learning exchanges between teacher and student, and student to student, (e.g. scaffolding? collaborative work? mental model building? developing learner’s identity? etc.) that this generation of MOOC developers do not have any sense of at all.

MOOCs for informal learning are fine, and having 7% pass rates out of 100,000 students are just fine when there are few stakes attached. But as we saw with the San Jose State pilot, once we put stakes on a MOOC course (e.g. students get credit for these classes that impact their futures), the bar for accountability increases. If we slam our education systems (K-12 and higher education) for mediocre student outcomes, then the same evaluation should be applied to MOOCs as well.

But MOOCs clearly are “something”. What is it then? If we think about MOOCs as another sociotechnical system, we can begin to articulate some immediate low hanging fruit for research, identify what we need to know going forward, and maybe move on in the hype cycle.

A sociotechical system is a combination of people, contexts, and the artifacts we employ (like technology) to enact new social practices. Understanding the intersections of these concepts help us sharpen our thinking about the design, use, and effects of new technology or social practices. For example:

Learning. Learning is complex. It really is. Trust me. Whole fields of study dedicated to Education, Pyschology, Learning Sciences attest to this. If we truly appreciate this proposition that learning is complex, then it’s clear that MOOCs solve one element of learning (delivering free content at scale), so we should give them props for that. But MOOCs haven’t yet approximated the rich interactions that occur in face-to-face settings that are important for learning: things like identity, social cooperation, project-based experiences etc.

Great, so should we just abandon this experiment? I’d say no, this realization crystallizes very clear research needs.If you’re more inclined towards the technical aspect of the sociotechnical system, get to work on designing ways to model effective learning practices in MOOC environments.

Taking this research stream seriously means not saying things like “we added forums for social learning” and “we put quizzes in there so it’s personalized now” or “we used peer-grading” (which solves an important but only one functional aspect of a course, the need for teachers to grade stuff). It means we need to come up innovations that truly model deep learning experiences that can scale out. Or admit honestly that some important learning experiences CANNOT SCALE. Read some literature. Talk to some interesting folks who do learning research on aspects other than cognition or information transfer (like identity, discourse, sociocultural perspectives etc.)

Learning at Scale. So the big thing about MOOCs is we can finally do learning at scale!!! Um, well we do have this other “technology” that educates 80 million people at a time in the U.S. It’s called the education system. If we think about these two competing technologies as sociotechnical systems, we can start to appreciate what’s really different.

The U.S. education system as a sociotechnical system is many things. For example, It’s over 13,000 school districts and nearly 100,000 schools. Each entity is it’s own complex sociotechnical system of people, curriculum, resources, culture etc. These entities reside in society – different neighborhoods with different levels of socioeconomic hardship, ethnic and racial cultures etc., and these factors HUGELY impact what happens in a given school and the student outcomes. The education system has politics. So decisions like wanting every student to pass a basic skills test, and holding schools accountable for that, affects how the learning happens in this system. These social factors interact with technical factors (school buildings, resources, curriculum, tools etc.) and matter ALOT.

What do we know about MOOCs? Well they replace some aspects of the education system (like districts, schools, classrooms etc.) with others (for-profit startups, public-private partnerships between providers and school systems etc.). We don’t have entities like states, districts, neighborhoods and schools. But they’re instead replaced by entities like Coursera, Udacity, edX, and others. What’s different about this exchange of players?

We have tons of research in education policy, administration, organization etc. that help us understand the affordances and constraints of our education system, but we need more research and scholarly thought to articulate the repercussions of replacing those entities with different ones (MOOC providers).

We’ve seen initial pilots that begin to blend MOOCs with the traditional education system, like California trying to offer MOOCs for credit in community colleges. Now we really need to understand the SOCIO-technical system.

You mean students in remedial math at community college maybe aren’t the best candidates to read/watch content on their own and take quizzes, that maybe they need alternative teaching methods to help them? (e.g. they’re in remedial math for a reason, because traditional teaching methods didn’t work for them). What a finding (sarcasm)!!

I can understand when education scholars respond in snarky ways to these realizations. We should be more thoughtful ahead of time and understand the research on these issues when designing these types of sociotechnical partnerships (MOOCs, public education, diverse student populations, community colleges as a context etc.).

The Way Forward?

I’ve largely been safe from these high profile experiments because I’ve done most of my work with open education platforms (The Peer 2 Peer University) that do large-scale learning, but do not have the profit-motive or institutional aspirations of MOOC ventures. P2PU isn’t interested in giving out degrees and getting rich. So we’re able to experiment at the margins and do studies that improve our understanding of the different aspects of the sociotechnical system that is open education online… I think we need more experiments, and many of them rapidly, right now that can quickly further our knowledge of how to design these learning environments (and understand what we cannot replicate in terms of learning in these environments), in low-stakes settings like informal learning situations. We need knowledge quickly.

But, I also appreciate the ventures and experiments (like Georgia Tech’s online CS master’s degree) that are trying to bring large-scale online learning to institutions. But in these experiments, I think we need a broader appreciation of how learning interacts with social/cultural factors — the education research is replete with insights about this, and before we dive head-first into ill advised policies (like California giving credit for MOOCs) and pilots (San Jose), we need to convene teams of people who can help MOOC providers, policymakers, and institutions (e.g. university decision makers) understand the potential pitfalls of their ideas.

Controlling for this reasoned planning process (which almost never occurs well), we need small pilots that minimize detrimental effects on students (e.g. what are all those San Jose students who failed the MOOC going to do now?), but give us knowledge about who MOOCs best serve, and under what institutional/social/socioeconomic/cultural conditions MOOCs might work well.

It would be a mistake to slam MOOCs as part of our educational future. But I’d like to bypass the trough of disillusionment and get moving on to the slope of enlightenment.